Overview

This project was about designing and developing an app, that aims to solves a need for a common problem amongst college students. The problem we tackled was the issue of having a hard time choosing a place to eat. The design is actually fairly crude due to lack of time, as we previously had a totally different app design and purpose before changing to this due to limitations in our developing skills.

Role

Project manager

UX Designer

UX Researcher

UX Designer

UX Researcher

Tools

Storyboards, paper prototypes, human centered design, Photoshop, InVision, Google Survey.

Team

CHALLENGE

Our design opportunity is to help increase and improve the safety and awareness of those on the UCSD campus. The challenge was to provide a more coherent and salient approach to addressing issues on campus ranging from faulty lighting to robbery. We seeked to provide a way for prevention and efficient action to reports made by students and faculty so that they may be addressed accordingly.

NEEDFINDING

We conducted in-person interviews consisting ofundergraduate students, both male and female, ranging from the ages of 18 - 25. The majority of interviewees responded that while they did indeed feel safe on campus, if there was a method to improve it, it would be during nighttime hours.

One interviewee, Aimee, a third year student, noted that while she did feel safe on campus and did not think anything would happen, it was still “creepy” at night in some places. In addition, we also interviewed Adrian, a student volunteer at the UCSD police department. The information he provided further supported that the majority of incidents happen during nightfall and are usually on areas that are darker. These interviews seemed proving enough that safety at night was a primary need, with lighting being a major factor.

One interviewee, Aimee, a third year student, noted that while she did feel safe on campus and did not think anything would happen, it was still “creepy” at night in some places. In addition, we also interviewed Adrian, a student volunteer at the UCSD police department. The information he provided further supported that the majority of incidents happen during nightfall and are usually on areas that are darker. These interviews seemed proving enough that safety at night was a primary need, with lighting being a major factor.

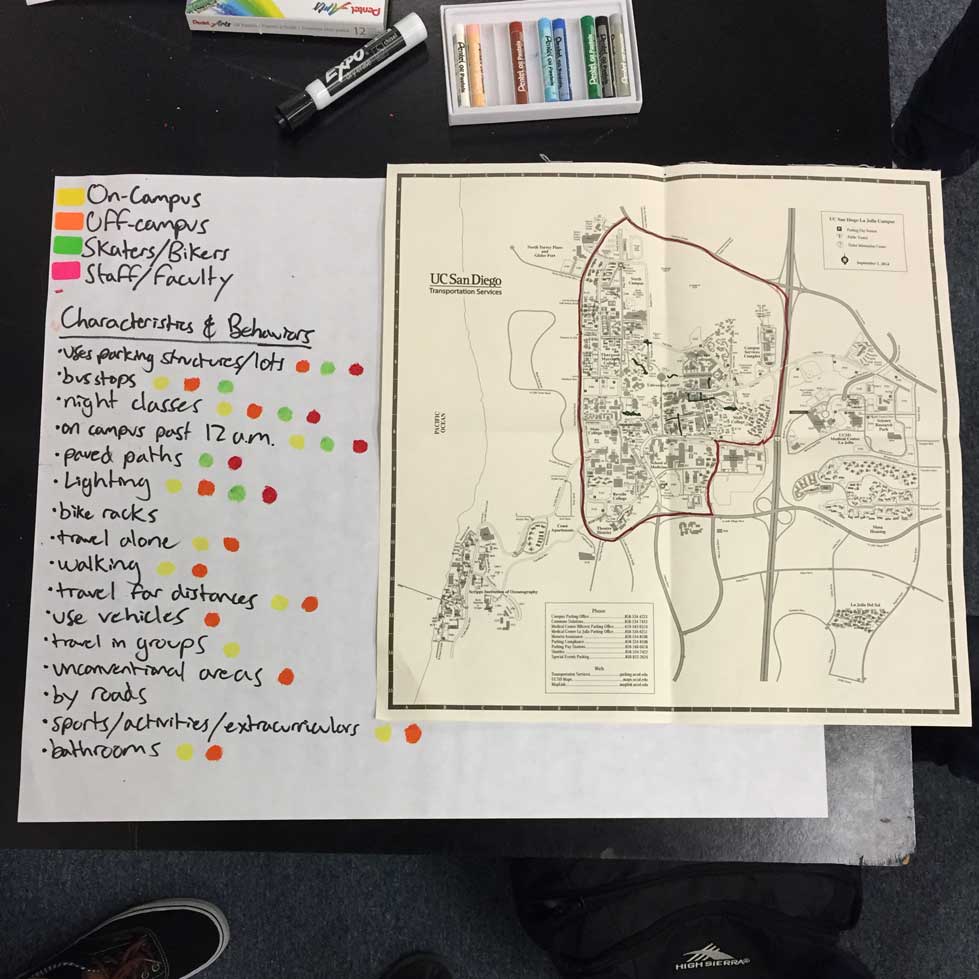

TARGET AUDIENCE

We ultimately decided upon four categories that would best represent the UC San Diego campus: on-campus students, off-campus students(commuters), bikers/skateboarders, and staff/faculty members.

On campus students are defined as current UC San Diego students who live on the UC San Diego campus. Many of these students attend classes, extracurricular activities, venture to work, and even travel off campus at times. Most of these students walk instead of using any vehicles, which means that safety would be a really important factor to them because there is very little protection and prevention when one is walking, especially alone.

Similarly, off-campus students also share the same characteristics, albeit that they tend to travel farther off-campus to parking lots, and other areas nearby campus, such as where their cars are parked in both residential and/or commercial areas.

Bicyclists and skateboards are also similar to the other two above categories because they can considered to be a subset of on-campus and off-campus students, but with better mobility due to possessing a faster form of transportation than simply walking.

Staff and faculty are very similar to on-campus and off-campus students, but they tend to park closer to main areas of campus. However, they may have to travel to obscure places at obscure times whether it be to their labs, classrooms, or even to other regions of campus itself. This campus has over 30,000 people on it and the maintenance of it could be required of them at anytime anywhere.

On campus students are defined as current UC San Diego students who live on the UC San Diego campus. Many of these students attend classes, extracurricular activities, venture to work, and even travel off campus at times. Most of these students walk instead of using any vehicles, which means that safety would be a really important factor to them because there is very little protection and prevention when one is walking, especially alone.

Similarly, off-campus students also share the same characteristics, albeit that they tend to travel farther off-campus to parking lots, and other areas nearby campus, such as where their cars are parked in both residential and/or commercial areas.

Bicyclists and skateboards are also similar to the other two above categories because they can considered to be a subset of on-campus and off-campus students, but with better mobility due to possessing a faster form of transportation than simply walking.

Staff and faculty are very similar to on-campus and off-campus students, but they tend to park closer to main areas of campus. However, they may have to travel to obscure places at obscure times whether it be to their labs, classrooms, or even to other regions of campus itself. This campus has over 30,000 people on it and the maintenance of it could be required of them at anytime anywhere.

DESIGN PROCESS

During the design process, our design solution was changed and modified numerous times as a response to the data that we obtained and aggregated. Originally, we were planning on implementing a method to address the poor lighting situation of the UC San Diego campus at night. With regards to that solution, we scoured the campus and mapped out areas with inoperative lights or areas that seemed quite dark. Our solution would be to somehow create a self-sustaining lighting system that provides lighting campus-wide, especially in dark areas. However, after speaking to faculty, we discovered there were already implementation and plans for addressing the lighting issues on campus, called the Microgrid system.

1ST ITERATION

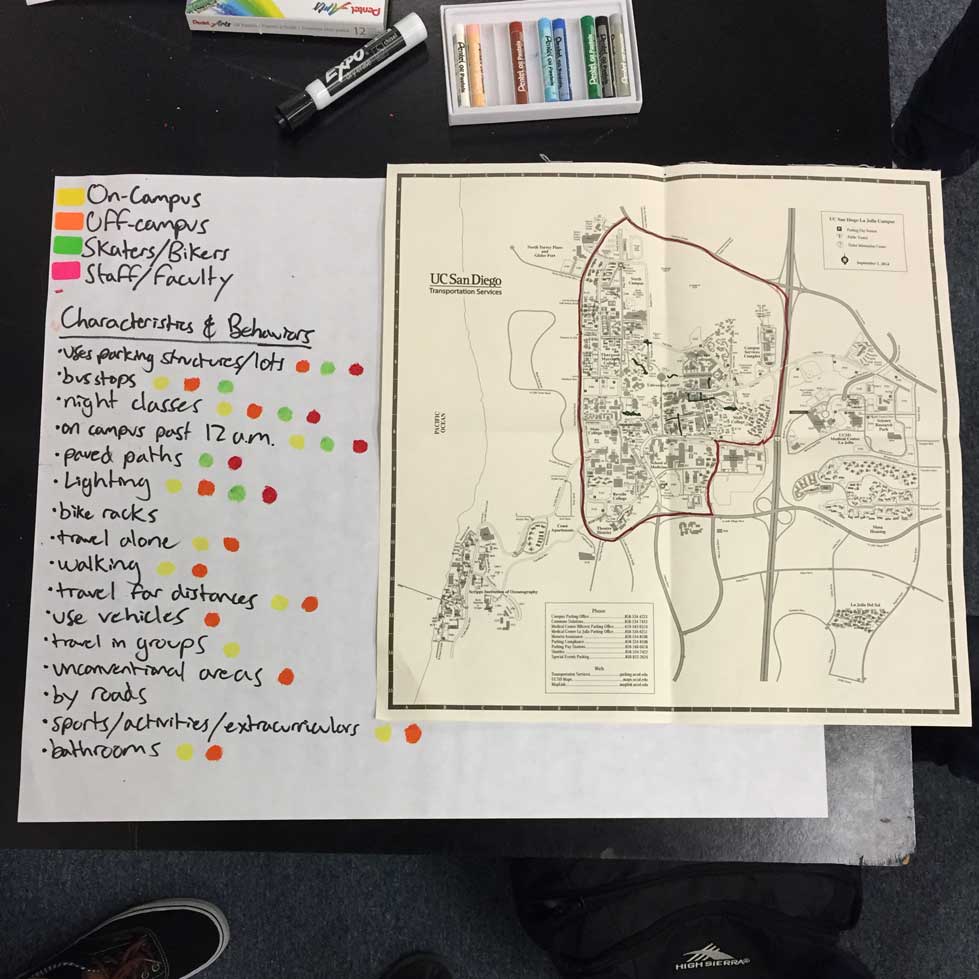

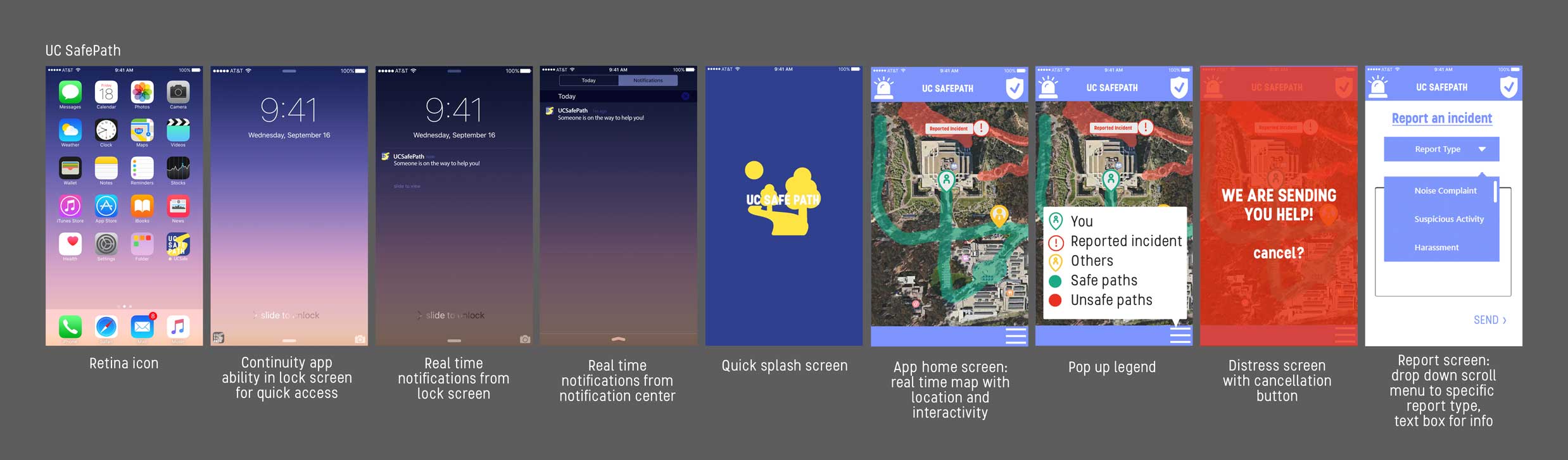

After dropping that idea, we pivoted towards the basics of safety: asking for help. This prototypes main feature was an emergency response button:

that would be quickly accessible through an application on a user’s phone. By pressing on this emergency button, the user would be able to send out a distress signal directly to the police dispatch along with the user’s current location that would be tracked by GPS. Furthermore, the prototype had features that allowed users to report incidents, to pinpoint incidents onto the map, as well as to see locations where other users have inputted or reported issues. We pursued this prototype for a significant period of time while producing two varying levels of prototypes: a lower and high fidelity mockup of the app. However, we received criticism that the app could easily be abused and may not be easy and fast enough to use in a real emergency.

2ND ITERATION

We pivoted again, to our second prototype which retained various features from our first prototype such as an emergency alert button, a method of reporting incidents, and a map that displayed various incidents that have been reported. The main differences was the shift of having the response button alert nearby students rather than police with the application.

The idea was for this to create a greater sense of safety amongst students, using student presence as a preventative measure rather than resorting to calling authorities as a first, which could be quicker and may combat against bystander effect. Furthermore the app would only be accessible to people on the UC San Diego campuses through either connecting it to the campus’ database or requiring sign up based on a @ucsd.edu email for example. While the idea and potential of crowdsourcing was very interesting and innovative, we once again had to pivot due to the various data that we analyzed to what is now considered our final design solution.

3RD ITERATION

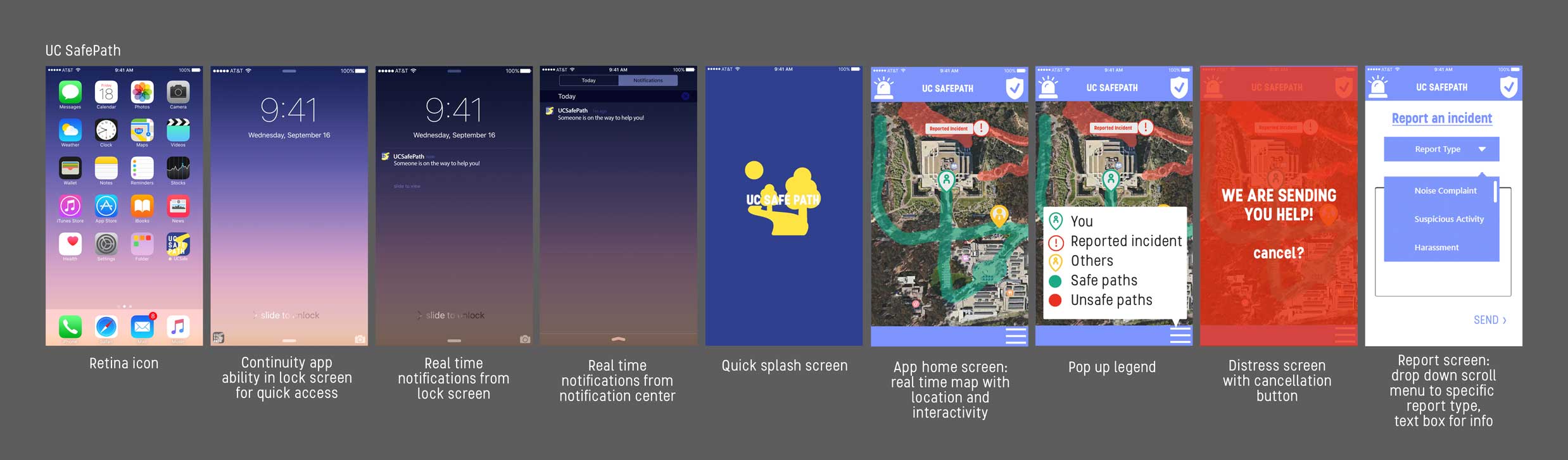

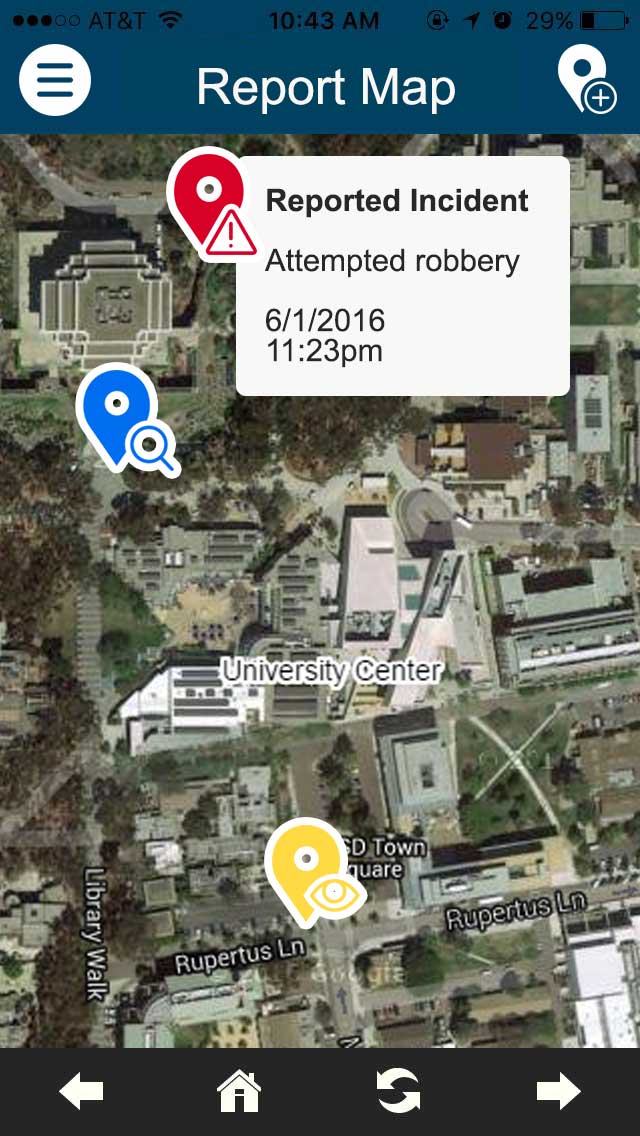

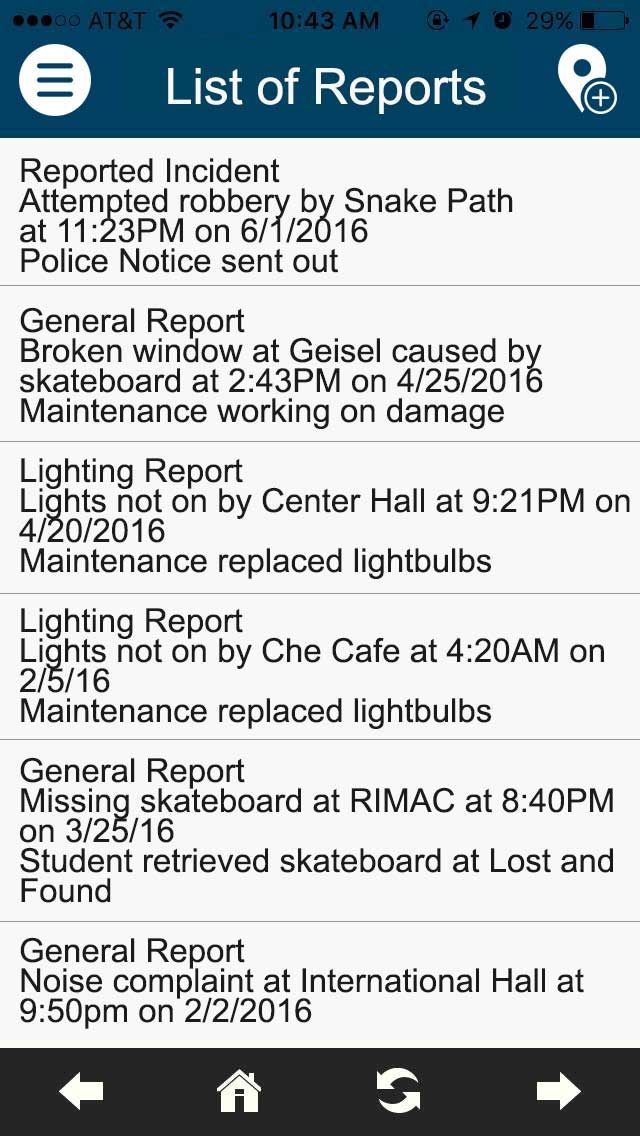

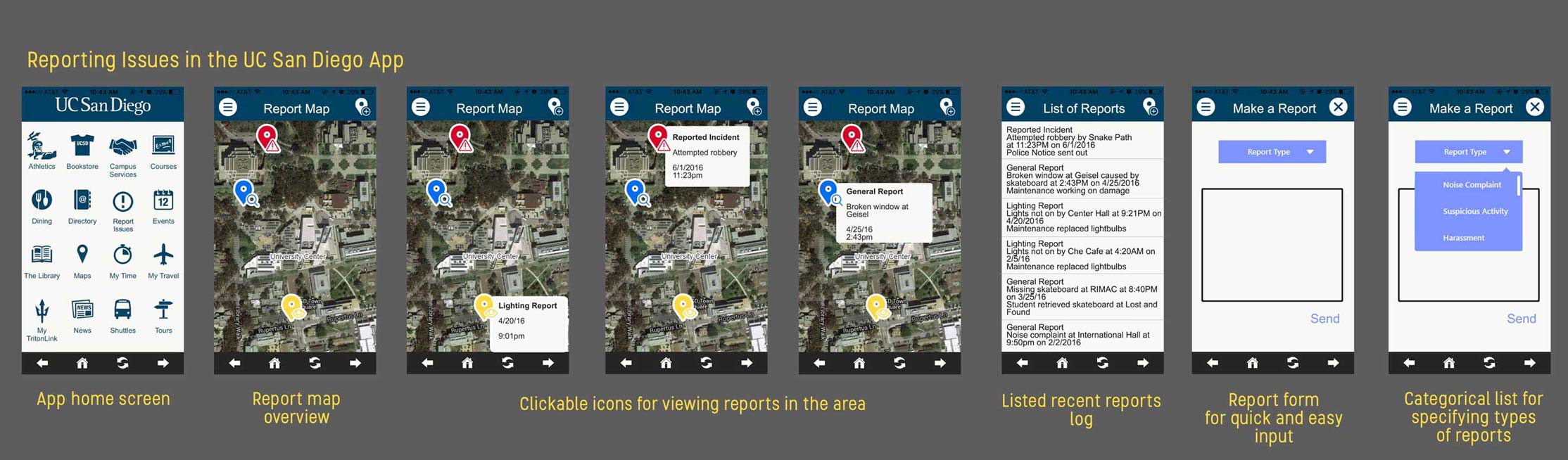

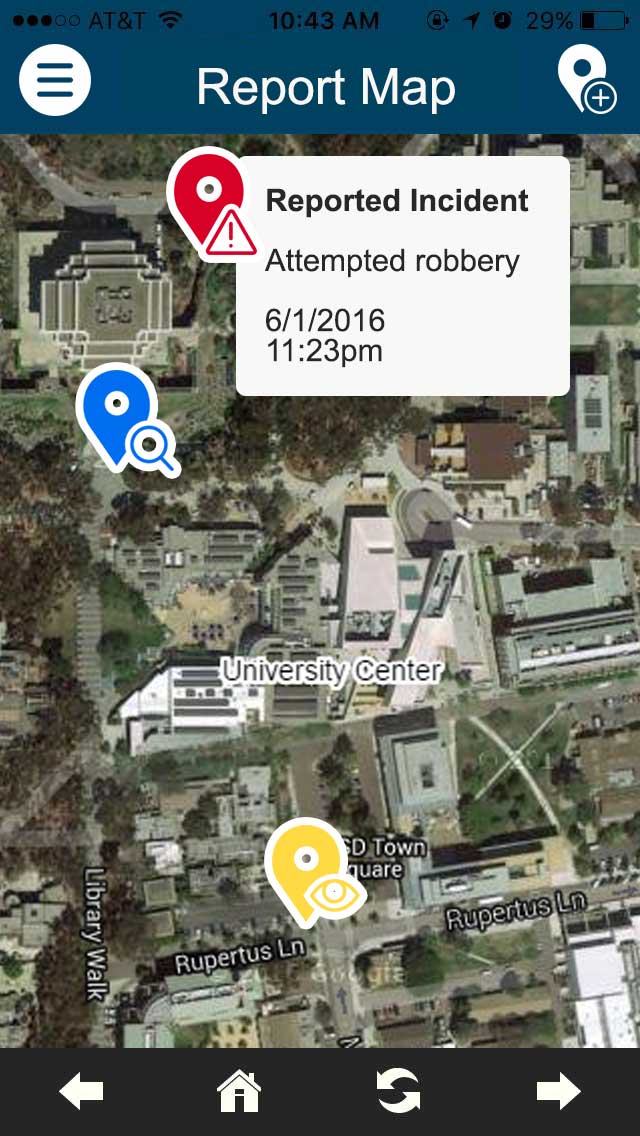

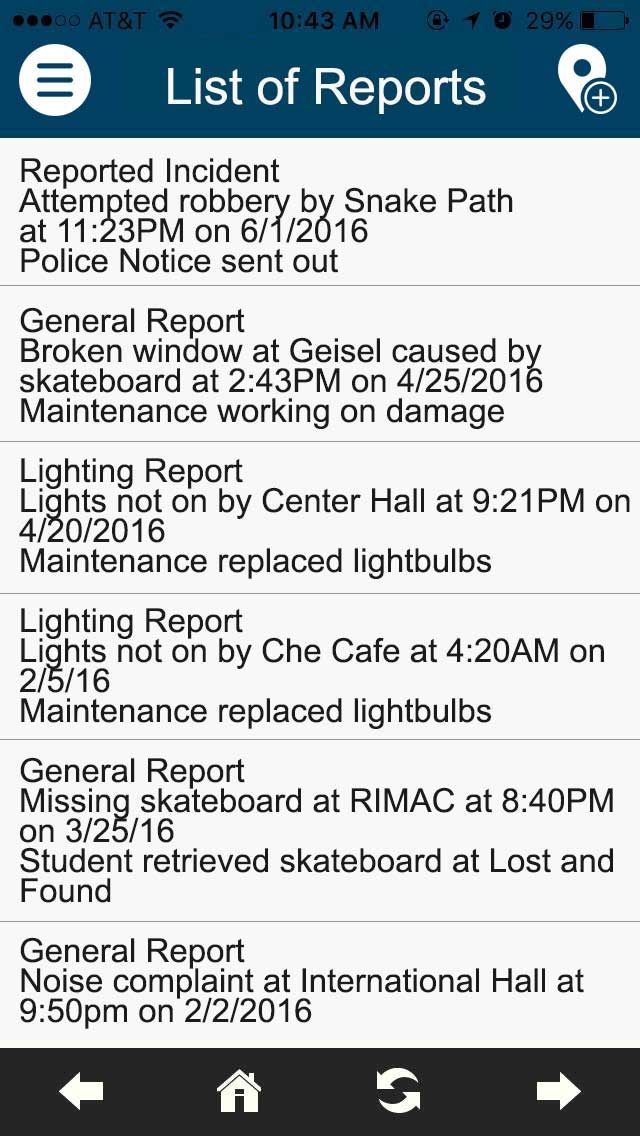

Our final design solution focuses on the concept of reporting incidents as a primary means to prevent future problems and promote safety through keeping people aware of the various problems that are on the campus. Our main function, this time, is utilizing the interactive map from the previous two iterations to display reported incidents which are color-coded based on what the issue pertains to, such as blue representing a maintenance or general problem, red representing a severe issue such as a robbery, and yellow representing a lighting issue. The reports can be seen by a map to visually see where the issue was located or by a list feed of recent reports.

This would take on the form of being an informational source to be used as a preventative measure, rather than a emergency response button. We also retained the ability from our previous prototypes to report issues at a consolidated location to mitigate the hassle of the numerous hotlines and websites that UC San Diego currently has implemented to address the varying physical and social problems on campus. We ultimately included these features because having a broader perspective on the reports that go on throughout our campus would give our students the power to be notified in real time, mitigating the chances or possibilities of running into unforeseen hazards.

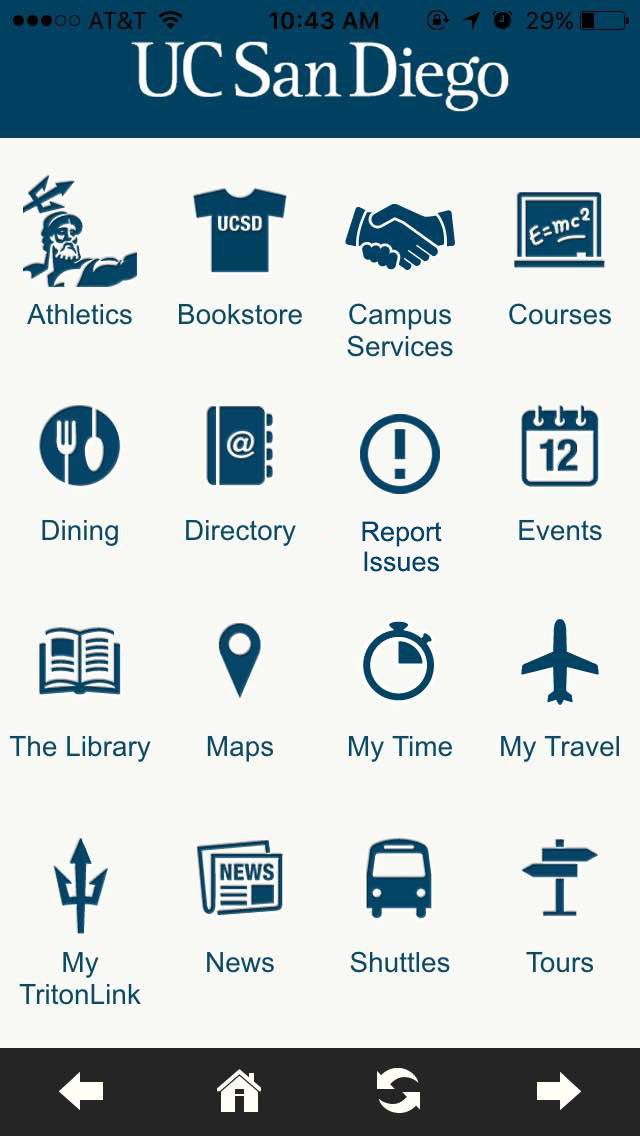

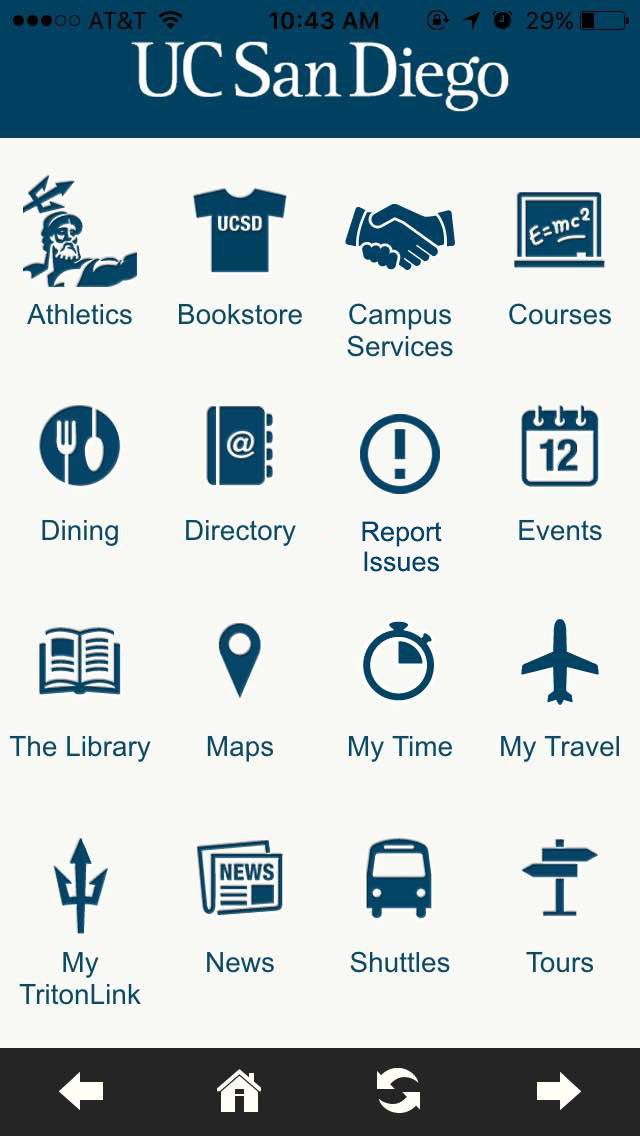

Additionally, the app that we developed would be part of the current Tritonlink app, being one of the various options that users could select. We decided to go with this mode of delivery rather than creating a whole different and separate app. Also in this way, the school could regulate incidents and hold users accountable for reporting false information and vice versa, users could hold the school accountable for not remedying the various problems and issues that get reported. Based on the types of incidents that the users report, the most relevant school department would get notifications regarding the incidents, and could then try to solve the issues.

Overall, our design solution focuses on safety awareness/prevention and appropriate reaction rather than the extreme situations that people typically imagine when thinking of, which is intervening or stopping crimes. After catering to our target audience, we wanted to produce a solution that has the ability to target most, if not all, people; and we decided on a phone application because people typically have phones that they carry and use all the time. Giving our students access to this service and informing them of its contributory features is essential for this applications efficacy. Our solution is valuable and important to our campus’ safety in a sense that it gives students a chance to discover and report safety issues on campus, serves as a neighborhood watch which would help prevent potential danger, while at the same time remedies an issue that UCSD unfortunately has, which is the difficulty of reporting problems in an efficient manner.

1ST ITERATION

After dropping that idea, we pivoted towards the basics of safety: asking for help. This prototypes main feature was an emergency response button:

that would be quickly accessible through an application on a user’s phone. By pressing on this emergency button, the user would be able to send out a distress signal directly to the police dispatch along with the user’s current location that would be tracked by GPS. Furthermore, the prototype had features that allowed users to report incidents, to pinpoint incidents onto the map, as well as to see locations where other users have inputted or reported issues. We pursued this prototype for a significant period of time while producing two varying levels of prototypes: a lower and high fidelity mockup of the app. However, we received criticism that the app could easily be abused and may not be easy and fast enough to use in a real emergency.

2ND ITERATION

We pivoted again, to our second prototype which retained various features from our first prototype such as an emergency alert button, a method of reporting incidents, and a map that displayed various incidents that have been reported. The main differences was the shift of having the response button alert nearby students rather than police with the application.

The idea was for this to create a greater sense of safety amongst students, using student presence as a preventative measure rather than resorting to calling authorities as a first, which could be quicker and may combat against bystander effect. Furthermore the app would only be accessible to people on the UC San Diego campuses through either connecting it to the campus’ database or requiring sign up based on a @ucsd.edu email for example. While the idea and potential of crowdsourcing was very interesting and innovative, we once again had to pivot due to the various data that we analyzed to what is now considered our final design solution.

3RD ITERATION

Our final design solution focuses on the concept of reporting incidents as a primary means to prevent future problems and promote safety through keeping people aware of the various problems that are on the campus. Our main function, this time, is utilizing the interactive map from the previous two iterations to display reported incidents which are color-coded based on what the issue pertains to, such as blue representing a maintenance or general problem, red representing a severe issue such as a robbery, and yellow representing a lighting issue. The reports can be seen by a map to visually see where the issue was located or by a list feed of recent reports.

This would take on the form of being an informational source to be used as a preventative measure, rather than a emergency response button. We also retained the ability from our previous prototypes to report issues at a consolidated location to mitigate the hassle of the numerous hotlines and websites that UC San Diego currently has implemented to address the varying physical and social problems on campus. We ultimately included these features because having a broader perspective on the reports that go on throughout our campus would give our students the power to be notified in real time, mitigating the chances or possibilities of running into unforeseen hazards.

Additionally, the app that we developed would be part of the current Tritonlink app, being one of the various options that users could select. We decided to go with this mode of delivery rather than creating a whole different and separate app. Also in this way, the school could regulate incidents and hold users accountable for reporting false information and vice versa, users could hold the school accountable for not remedying the various problems and issues that get reported. Based on the types of incidents that the users report, the most relevant school department would get notifications regarding the incidents, and could then try to solve the issues.

Overall, our design solution focuses on safety awareness/prevention and appropriate reaction rather than the extreme situations that people typically imagine when thinking of, which is intervening or stopping crimes. After catering to our target audience, we wanted to produce a solution that has the ability to target most, if not all, people; and we decided on a phone application because people typically have phones that they carry and use all the time. Giving our students access to this service and informing them of its contributory features is essential for this applications efficacy. Our solution is valuable and important to our campus’ safety in a sense that it gives students a chance to discover and report safety issues on campus, serves as a neighborhood watch which would help prevent potential danger, while at the same time remedies an issue that UCSD unfortunately has, which is the difficulty of reporting problems in an efficient manner.

Competitive Analysis

While this app has many strengths such as being able to appeal to users on a more general basis than extreme incidents, consolidation of reporting issues, and even possibly holding the school accountable for not alleviating issues, there are nevertheless limitations involved with implementing a solution such as this. For example, there are other numerous safety apps that have similar functions such as bSafe and React mobile which allows you to send emergency signals to contacts user have pre-approved. Competitive analysis between other safety apps and our design solution highlights possible confounds such as being much less personal, considering that the report would go to the appropriate district department rather than a personal contact that is user inputted. While the school may realize there are issues such as potholes or broken lights, they may not actually do anything about it, causing the issue to continually persist. Also, this app is based upon users actively reporting various issues they discover. If no users report, the knowledge of the problem is not disseminated and no benefit could come about from this application.

Nevertheless, this app is incredibly valuable in its use of being able to address major and minor issues in real time. Instead of looking all over to find different departments and websites to report different issues, users of this app could report problems directly to our system, which will then categorize the incidents based on the type and send the reports out to the correct department responsible. Unlike the other competitors mentioned above whose apps may not be used as often as it really depends on the user, our app’s ability to address minor issues can be incredibly vital to the livelihood of the people of our campus. Reports of small potholes in the ground may not top the charts of people’s safety list, but by simply bringing about awareness and the realization of them could possibly prevent someone tripping or a flat tire, which could prove to be quite beneficial the community as a whole. Finally, with regards to the necessity of users collaborating, through in person interviews, many believed that if the apps feature was more transparent such as being mentioned in emails or during orientation it would greatly influence and encourage increased participation. This means that further advertisement would be needed if the application really hits the market.

Nevertheless, this app is incredibly valuable in its use of being able to address major and minor issues in real time. Instead of looking all over to find different departments and websites to report different issues, users of this app could report problems directly to our system, which will then categorize the incidents based on the type and send the reports out to the correct department responsible. Unlike the other competitors mentioned above whose apps may not be used as often as it really depends on the user, our app’s ability to address minor issues can be incredibly vital to the livelihood of the people of our campus. Reports of small potholes in the ground may not top the charts of people’s safety list, but by simply bringing about awareness and the realization of them could possibly prevent someone tripping or a flat tire, which could prove to be quite beneficial the community as a whole. Finally, with regards to the necessity of users collaborating, through in person interviews, many believed that if the apps feature was more transparent such as being mentioned in emails or during orientation it would greatly influence and encourage increased participation. This means that further advertisement would be needed if the application really hits the market.

CONCLUSIONS

We began our research by conducting preliminary interviews, introducing simple questions to discern our interviewees experiences and concerns of campus safety at night. We primarily interviewed various undergraduate students of a variety demographics: ages ranging 18 - 25+, gender, ethnicity/race etc. These initial interviewee subjects amounted to 14 each since we did around 2-3 per group member, typically comprised of our friends, however some group members had other occupations such as being a bus driver and a library assistant so some interviewees were people who used the above services. In addition to this, we also split up as a team and began exploring our actual campus during nighttime hours. This led our team to be more informed of the potential issues that we would need to address.

We discovered that most answers from our interviewees tend to be similar, showing a trend in certain characteristics. Most answered the questions similar to how Aimee felt as mentioned above, stating that they find the campus to be fairly safe at night, although this depends on the part of campus, as the more well known areas tend to be perceived to be the safest, while we found that areas poorly lit and more secluded to be perceived as less safe. For our prototype, we came up with the idea of developing an emergency button because during our travels around campus we spotted various blue emergency call boxes widely scattered throughout that seemed to be unfunctional. During the talk with the receptionist, we discovered that the call boxes do work, however, the signal gets sent to the receptionist and then relayed to the police. We thought this process was incredibly cumbersome as well as unreliable. We also asked a small subset of people around the campus, around 5, if they knew how to use the call box. None knew.

During a class activity where we shared prototypes with other groups, two out of the two groups we discussed our prototype with, thought that the idea of an emergency button could be easily abused.

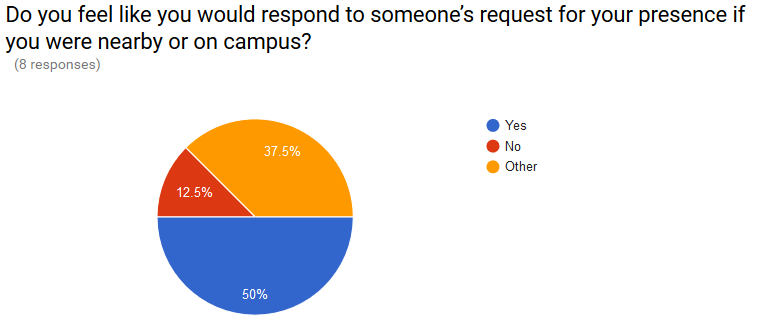

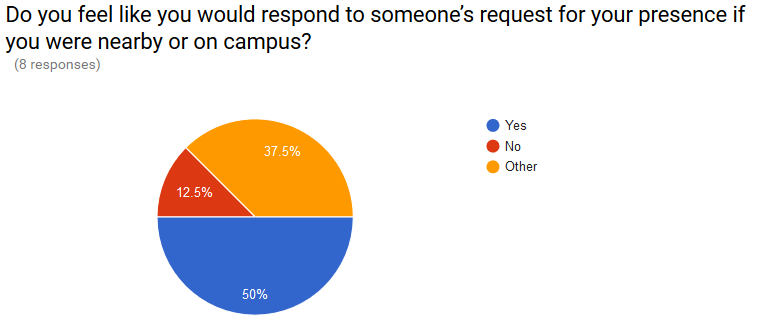

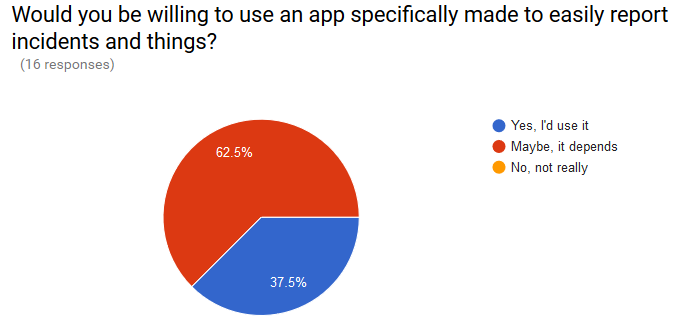

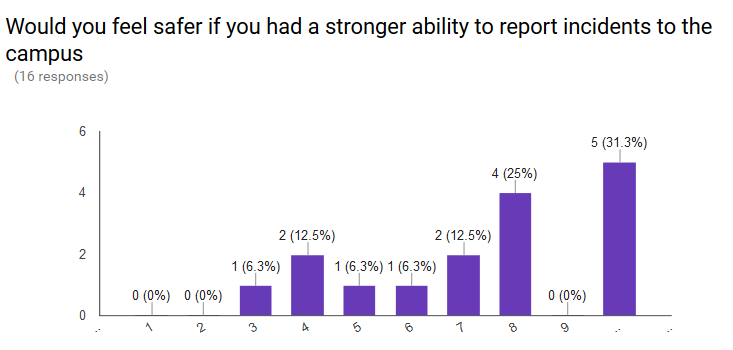

Due to the simplicity of how it is activated, by a single click, a person could accidentally “butt - dial” said one of the group members. Additionally another group member commented that, “Do you really want the police to have to determine which incidents are actually severe?”, “there is no method to filter what really requires police intervention and people simply overreacting”, and “Why are you trying to make people stray from simply calling 911?”. These comments proved to be quite critical and ultimately caused us to pivot our design. After brainstorming we decided to retain the feature of an emergency button, but instead of resorting police, we wanted a method to alleviate their burden and place taking action within the hands of students via crowdsourcing. We collaborated extensively with one of the TAs, Michael and he brought up various evidences of crowdsourcing being successful such as neighborhood watches. Running with the idea, we released surveys to gauge the likelihood and willingness of students to take charge for themselves to make a difference. While our sample size was quite small, 8 people, many of them were willing to be proactive in assisting students.

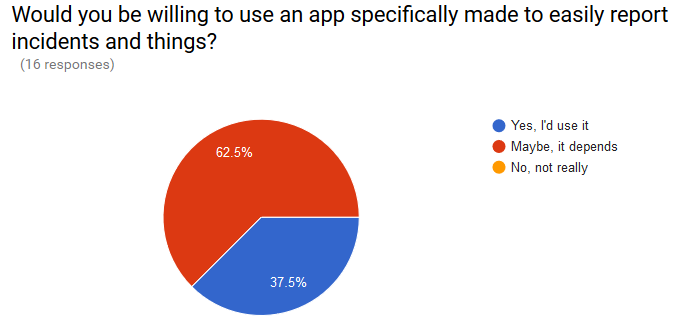

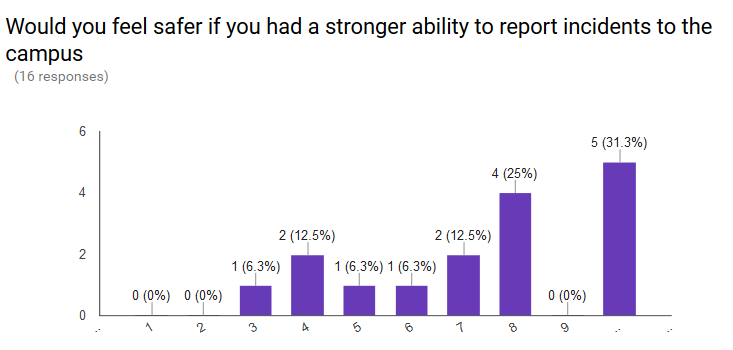

It seemed as if we were going in the correct direction and we wished to support our information with more evidence through in person interviews. We again interviewed a small set of people, around 5, and discovered that it was quite the opposite. One response by Wilson (age 20), stated that he would consider going, but if he was too busy he would hope that others would take the initiative instead. Another response by Tuan (age 25), remarked that if there was someone getting robbed by a weapon, what could he honestly do? Additionally one of our team members who applied to be a campus security officer, CSO, remarked that when he was getting trained they were told to avoid problems such as this and instead radio in help, etc. If people whose duty was to assist with safety were told not to help out in situations such as a robbery, how could we believe that other random students would want to. Furthermore, through more class activities such as the gallery walk, one TA, Stephen, exclaimed that it would be quite creepy having random students monitor and then respond to an emergency signal. Also, some students during the gallery walk believed that even if other students came, would they actually do anything because our app was essentially falling into the trap of the bystander effect. In light of the criticism and evidence, we knew we had to pivot once again. Throughout each of our prototypes starting from the app onward, we continually integrated the feature of having the ability to report issues and display these on a map. While our other functions were disliked such as the emergency response button, many from interviews, surveys, and even students from class thought that the reporting feature would be a concept worth pursuing.

Due to how little time we had left, we were only able to conduct an online survey and the results proved to be quite fruitful. While the current survey proved to be successful, there was discussion with some of the teaching staff, that this solution may not effectively promote safety. If we had more time we would continue to have in person interviews and simply continue to iterate, iterate, and iterate. Safety is such a broad and general concept that ultimately proved difficult to address and may actually be an impossible topic to fully satisfy. However, we did learn immensely from this experience such as, we should have listened to our audience initially and stuck with a lighting solution. Nevertheless, data has shaped our idea quite immensely from going to biking and skating safety to one akin to reporting various issues on campus.

Overall, this was my first design course and I was shocked by how much design can change and how feedback is highly critical. If we had not gained the feedback to pivot that many times, we could have ended up with a very poor design based on assumptions. I learned that pivoting was not bad, even if we had to pivot a week before final presentations. That is part of the design process, of iterate, iterate, iterate; where you can't rely on assumptions, you have to garner feedback and build off of what you learn from potential users. I believe we could have done better with gaining feedback and testing, because I felt we relied on assumptions at each stage of the process. I think that was the reason we had to pivot so much. I feel that I could've have also done better if I did more user research, wireframing, and low fidelity prototyping to create the design and architecture of the app. I instead went straight into it and built a design without any foundation or research. Without the proper research, and jumping into the design too quick, I set up problems along the way that were unnecessary.

We discovered that most answers from our interviewees tend to be similar, showing a trend in certain characteristics. Most answered the questions similar to how Aimee felt as mentioned above, stating that they find the campus to be fairly safe at night, although this depends on the part of campus, as the more well known areas tend to be perceived to be the safest, while we found that areas poorly lit and more secluded to be perceived as less safe. For our prototype, we came up with the idea of developing an emergency button because during our travels around campus we spotted various blue emergency call boxes widely scattered throughout that seemed to be unfunctional. During the talk with the receptionist, we discovered that the call boxes do work, however, the signal gets sent to the receptionist and then relayed to the police. We thought this process was incredibly cumbersome as well as unreliable. We also asked a small subset of people around the campus, around 5, if they knew how to use the call box. None knew.

During a class activity where we shared prototypes with other groups, two out of the two groups we discussed our prototype with, thought that the idea of an emergency button could be easily abused.

Due to the simplicity of how it is activated, by a single click, a person could accidentally “butt - dial” said one of the group members. Additionally another group member commented that, “Do you really want the police to have to determine which incidents are actually severe?”, “there is no method to filter what really requires police intervention and people simply overreacting”, and “Why are you trying to make people stray from simply calling 911?”. These comments proved to be quite critical and ultimately caused us to pivot our design. After brainstorming we decided to retain the feature of an emergency button, but instead of resorting police, we wanted a method to alleviate their burden and place taking action within the hands of students via crowdsourcing. We collaborated extensively with one of the TAs, Michael and he brought up various evidences of crowdsourcing being successful such as neighborhood watches. Running with the idea, we released surveys to gauge the likelihood and willingness of students to take charge for themselves to make a difference. While our sample size was quite small, 8 people, many of them were willing to be proactive in assisting students.

It seemed as if we were going in the correct direction and we wished to support our information with more evidence through in person interviews. We again interviewed a small set of people, around 5, and discovered that it was quite the opposite. One response by Wilson (age 20), stated that he would consider going, but if he was too busy he would hope that others would take the initiative instead. Another response by Tuan (age 25), remarked that if there was someone getting robbed by a weapon, what could he honestly do? Additionally one of our team members who applied to be a campus security officer, CSO, remarked that when he was getting trained they were told to avoid problems such as this and instead radio in help, etc. If people whose duty was to assist with safety were told not to help out in situations such as a robbery, how could we believe that other random students would want to. Furthermore, through more class activities such as the gallery walk, one TA, Stephen, exclaimed that it would be quite creepy having random students monitor and then respond to an emergency signal. Also, some students during the gallery walk believed that even if other students came, would they actually do anything because our app was essentially falling into the trap of the bystander effect. In light of the criticism and evidence, we knew we had to pivot once again. Throughout each of our prototypes starting from the app onward, we continually integrated the feature of having the ability to report issues and display these on a map. While our other functions were disliked such as the emergency response button, many from interviews, surveys, and even students from class thought that the reporting feature would be a concept worth pursuing.

Due to how little time we had left, we were only able to conduct an online survey and the results proved to be quite fruitful. While the current survey proved to be successful, there was discussion with some of the teaching staff, that this solution may not effectively promote safety. If we had more time we would continue to have in person interviews and simply continue to iterate, iterate, and iterate. Safety is such a broad and general concept that ultimately proved difficult to address and may actually be an impossible topic to fully satisfy. However, we did learn immensely from this experience such as, we should have listened to our audience initially and stuck with a lighting solution. Nevertheless, data has shaped our idea quite immensely from going to biking and skating safety to one akin to reporting various issues on campus.

Overall, this was my first design course and I was shocked by how much design can change and how feedback is highly critical. If we had not gained the feedback to pivot that many times, we could have ended up with a very poor design based on assumptions. I learned that pivoting was not bad, even if we had to pivot a week before final presentations. That is part of the design process, of iterate, iterate, iterate; where you can't rely on assumptions, you have to garner feedback and build off of what you learn from potential users. I believe we could have done better with gaining feedback and testing, because I felt we relied on assumptions at each stage of the process. I think that was the reason we had to pivot so much. I feel that I could've have also done better if I did more user research, wireframing, and low fidelity prototyping to create the design and architecture of the app. I instead went straight into it and built a design without any foundation or research. Without the proper research, and jumping into the design too quick, I set up problems along the way that were unnecessary.